This week, I have taken a break from Security Research, as I often like to do before I present at a conference, and focused myself on another area I love to explore. Music. I love music. Playing it, listening to it, recording and editing. It is all great fun. Recently though, I have wanted to push beyond my very basic understanding of music, and begin to understand 'why' certain concepts work, when and how they were introduced, etc. To do this I turn my attention back to Music Theory and an analysis framework from MIT called Music21.

This post will serve as a starting point for people new to the framework, but I will assume some level of theoretical understanding on the music aspect. There are plenty of excellent Music Theory courses online if these concepts are not familiar to you.

What is Music21? Well, simply put, it is a python library which defines all the classes of objects you might expect to find in a piece of music. This goes beyond simply notes, staffs and time signatures. It includes frequency information, MIDI codes, and structural relationships (which I will discuss more below).

Before we get started you must install a few pieces of software. These instructions assume a Linux environment. The library can work just as well on Windows or Mac. For those instructions you can refer to the official setup guide http://web.mit.edu/music21/doc/installing/index.html

You will want:

- The Music21 library itself.

- pip install –upgrade music21

- A MusicXML Editor. I use (and highly recommend) MuseScore

- apt-get install -y musescore

- A MIDI player For playing compositions directly from code.

Where to begin?

Music is made up of thousands of distinct little pieces. Most people zoom way down to the smallest molecular piece (a note) and start to build upward towards a piece of music. I am going to take the opposite approach and examine the structure of a song decomposing it downward into a single note. I think doing it this way will give you an advantage when you plan to use the library to do your own analysis.

|

| Song Decomposition |

Now that we have the song broken up and organized from a high level, let's look at how we can accomplish this using Music21. I thought it would be fun to write a piece of code which could compose a semi-random piece of music that would illustrate the core concepts of Music21. Plus, who doesn't want to have a Music fuzzer handy?

|

| Script initialization |

When composing a song, there are some basic decisions you need to make before you can start. First the most important decision, what is the FEEL of the song going to be? There are a lot of descriptions in Music Theory about the feel of a song. For example, the Major scale is described as bright, happy, upbeat, etc. By contrast the natural minor scale (Also known as Aeolin mode, which is derived from the major scale) is described as more melancholy and sorrowful. There are entire books on the subject of scales and modes which cover the topc in more detail. For now it is sufficient to say I want to stick with a bright, happy sounding song so I will stay with the major scale for now.

The next choice is often what key the song will be played in. I am going to assume a static song key for now. Although that is purely for easier understanding. Music21 can handle as many key changes as the Temptations can throw at it and more.

|

| Song Key Selection |

|

| Creating and displaying a score |

- A Score is a particular subclass of a Stream, which is not entirely necessary (for reasons which I will explain in a minute) but is suggested by the documents as a good standard practice, which I try to follow.

- A Part is a stream subclass which is intended to gather measures of music together into one related block. In my example I have called this Part the verse. Everything contained in this stream will be music related to the verse part of the overall song. Again, this isn't strictly required, but containing pieces in Parts objects allows you to take advantage of other features of the Score stream objects (like checking Score.parts parameter which returns a list of all the Parts objects within the Score stream.

- A Measure is a stream which is meant to be used to contain the notes which actually comprise the song. This is really just another convention and has no special use-case but is a good convention to follow.

The next two lines create a Metadata object, attach it to the Score object using score.append(), and finally update the Metadata.composer attribute which you will see the effect of below. The key thing to understand about the Metadata object is that is exists to help you keep organized, do searches, change presentation options, etc.

The next three lines choose a random key for the song, set it to the 4th octave (on a piano this is around Middle C), and conclude by updating the metadata object again. This time it adds a Dynamic title, based off of the chosen Key's name.

The For loop is where we will create and add the Note objects to the measure stream. Notes are the smallest unit in music. They are comprised of a pitch, a duration, and a strength. Assume for the moment we want all the notes to be played at a consistent strength, that means we only need to deal with pitch and duration. Music21 makes the process easy by collecting all the pitches contained in a given key in the Key.pitches attribute. This attribute contains a list of Pitch objects which can be referenced when creating Note objects. In fact, Note objects contain a Pitch object inside them. For now, it is only important to understand that notes are objects in memory. Because of this you cannot attach the same Note object multiple times. instead you must create a copy of the note which will exist at a new memory address. Each note is created and then appended to the measure. The default duration for a note is a quarter. I will discuss durations more in a moment. The final bit of the code adds the measure to the part, adds the part to the score, and finally calls the .show() function to open the external viewing application. Now lets run it and see what we get

|

| MuseScore output generated |

|

| Making a melody generator in Python |

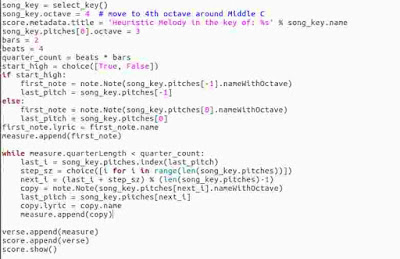

The algorithm above is a simple way of constructing Arpeggios. Currently, everything is assumed to be in 4/4 time with each note being a quarter note. It also has no concept of a rest yet, but it is getting more musical already.

|

| Heuristically Generated two bar melody |

Inside the code, when we create a note object let's also choose it's .duration.quarterLength property. Since a quarter note has a quarterLength of 1, we can say an eighth note should have a quarter length of 0.5. Now, i just randomly chose to weight my algorithm to favor quarter notes 2:1 but later I may look at setting this value based off of a statistical analysis of some meaningful section of the musical corpus.

|

| Weighted note duration selection added |

|

| A heuristic melody generated by the algorithm |

No comments:

Post a Comment